And from National Catholic Review, comes this article, sent to me by Jane, it's long but if you are interested in the subject worth the time:

On Behalf Of NCRonline.org

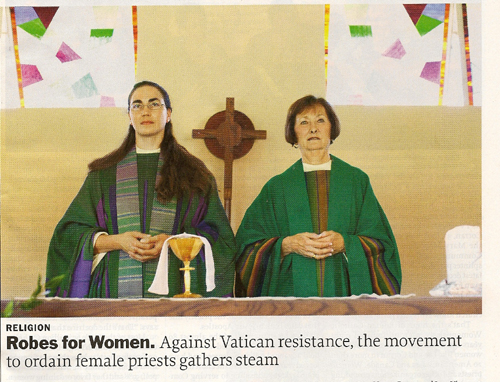

'Claim Roman Catholic,' says woman priest

Sep. 21, 2010

By Tom Roberts

In a 2006 file photo, Jane Via of the Mary Magdalene Apostle Catholic Community says Mass, assisted by Rod Stephens, a laicized Catholic priest. (Newscom/ZUMA Press/Jim Baird)

SAN DIEGO -- As a 5-year-old child of Presbyterian parents, Jane Via was deeply attracted to the 1950s Catholicism of her friends in her St. Louis neighborhood. That initial allure, however, was the start of a journey of faith that ultimately led her to a position of deep conflict with the authorities in the church she had grown to love.

The 62-year-old Via converted to Catholicism as a young adult. Decades later, she was ordained, first as a deacon in a 2004 ceremony on a boat in the Danube River, and then as a priest in 2006 on another boat, this time in Lake Constance, which has a shoreline shared by Switzerland, Germany and Austria.

Church authorities, of course, would say she is not ordained but rather self-excommunicated. She would reply otherwise, as she did in a July 19 interview here with NCR.

While the situation reaches the “either/or” stage rather quickly in conversation, the reality is something more complex and considered.

It is no little irony that the woman who now leads Mary Magdalene Apostle Catholic Community of 150 members (she makes her living, by the way, as a lawyer with the San Diego district attorney’s office) was smitten with the “concrete” reality of the Catholicism of her childhood.

How did she get the inclination, at age 5, that she wanted to be Catholic?

She said she grew up on a block where there were a lot of little Catholic girls “who ran back and forth, up and down the street, a little pack of girls who all played together. In those days, Catholics couldn’t go to Protestant churches, but Protestants could go to Catholic churches. So if I spent the night at a friend’s house on Saturday night, I went to Mass on Sunday morning. That’s how I was exposed to Catholics, through my friends who went to Catholic schools, played on Catholic baseball teams in the summer, went to confession every Saturday.”

Catholicism’s balance

It sounds like a contemporary argument for renewed emphasis on Catholic identity. But the attraction back then for the budding scholar and daughter of two well-educated parents was a balance to what she perceived as the “very intellectual” approach of the Presbyterian church. “I need spirituality to balance out my kind of spontaneous, intellectual approach to religion,” she said. She found in Catholicism a “balance of symbol, ritual, gesture. ... So I don’t know if it was so much Catholic identity as it was that it filled a huge gap in my life.”

Asked if the 5-year-old on the same block today would feel the pull, she said she didn’t know. “I guess it would depend on the 5-year-old. ... The world has changed so much. I mean the Presbyterian church has changed a lot, too.” She believes that the future of the church will be “not just ecumenical but much more transdenominational. There’s going to be a lot of moving in between -- people will tend to worship perhaps out of their historical tradition or out of a tradition that they choose.”

Her early fascination with Catholicism never went away. In a reversal of the usual go-to-college-and-leave-the-church routine, she went to Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., and became a Catholic. She didn’t tell her parents until she graduated and by then, she said, “I was 21, I was off to graduate school, I was leaving home.” Her parents weren’t happy, she said, but her father, “really the person of faith in our family,” wrote her a letter saying he honored her choice even if he wasn’t happy with it.

Having earned an undergraduate degree in Spanish language and literature, she went off to Marquette University in Milwaukee for a five-year program for a doctorate in theology.

But a turning point occurred before that, during her junior year of college, when she spent a semester in Spain studying theology with Jesuits and living in an Opus Dei household. While one can hardly expect Opus Dei to cheer the direction she’s taken, she said she found “many wonderful things about the structure of Opus Dei,” while simultaneously gaining new and progressive theological insights from the Jesuits who taught the theology courses at the college she attended.

Following Marquette she got a teaching job at Mercy College in Detroit, at a point when she also decided she wanted to be a lawyer. But she couldn’t afford the tuition on her teaching salary.

She taught there for three years before taking a job at the University of San Diego, a Catholic institution, teaching religious studies. One of the attractions that sealed the deal was when she learned that she could attend the university’s law school for free, and she did.

That turned out to be a good decision because, as she tells it, she was an early casualty of the political culture wars. In 1984 she signed a New York Times ad supporting vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro, who had drawn fire from the late Cardinal John O’Connor because of her support for legalized abortion. “There were priests who were threatened and nuns who were threatened” for signing the ad, she said, “but I was the only academic who was told, ‘Either retract your name or you’re done.’ ”

By then she was practicing law and teaching part-time and she told the school, “I’m really sorry, but I can’t take my name off.”

‘Radicalizing’ research

The stint at the University of San Diego, however, contributed to her future in ways other than a law degree. When she took the job she was told that she had to teach scripture because her emphasis had been in New Testament studies. “Little did I know how it would radicalize my life, because the contrast between what I learned in graduate school in a Catholic context and what I learned when I had to teach myself how to teach the New Testament was radicalizing.”

She was becoming increasingly aware of women’s issues and recalled that at Marquette, at one point, she had been introduced to a group of people as “This is Jane Via. She’s the ornament in our department.” She said she was probably the youngest female in the department.

The comment was made by “one of the Jesuit guys who I went to school with and liked very much, but that’s how they perceived my place there. I was not really perceived as someone who could probably go on to become a great scholar, and I carried that with me.”

When she began teaching the New Testament, she said, she realized that “what we’re taught as dogma does not come from the New Testament in many, many cases. Specifically with regard to women.” She said what she discovered was “that Jesus was essentially a feminist in his own time, that he traveled with women, he supported himself from their possessions, he ministered to women, he taught women. It was just mind-blowing.”

In 1982, she earned her law degree and was married that same year to Philip J. Faker, a financial planner and investment advisor and “Jane’s biggest fan.” Faker has his own Catholic story. Via describes him as “a driven-away Catholic,” largely because of an incident of deep betrayal of one of his family members by a priest when he was a child.

He missed all of the Second Vatican Council era in the 1960s and refers to his membership in a parish as a child as “kind of a community forced upon me by my parents” until he dropped out. He said his involvement with the Mary Magdalene Apostle Community began by helping Jane set up the church. He said he enjoys the people “and I’m into it for reform. Jane has the talent and the ability and the skills to move the reform movement forward and to actually accomplish some things. I don’t have those skills, but I have the skills that she needs to help her do these things, so when it came time to start the church, I did the legal and the tax and the financial and all that stuff.”

If the church of the ’50s lured Via, she no longer has any nostalgia for those days. The future, she hopes, holds the possibility of “more parishes like the one that I am part of, where Catholics can find, as I like to say, worship with integrity.”

She won’t shrink from the Catholic tag. “Be Catholic,” she says. “Claim Roman Catholic, say, ‘We are Roman Catholic.’ You can say that we’re schismatic, you can say that we’re criminals, you can say that we’re heretics, you can call us anything you want, but we’re not going away. We claim Catholic, and we claim Roman Catholic, and yet we do it differently.”

She said her congregation strives to live Catholicism in a way “that allows us to have integrity about social justice, about equality, about gays and lesbians and their place in human culture, about our connection as Americans to the reality of our impact on the rest of the world.”

The difference, she would say, stems from the discoveries she made when she was preparing those New Testament courses. The central difference from institutional Catholicism as most of the world knows it is the direction in which “we think the Gospel of Jesus demands that [we] go” -- a direction that is “radically inclusive.”

No comments:

Post a Comment